Constructive and Inclusive Dialogue

Guide to Constructive and Inclusive Dialogue

Constructive and inclusive dialogue has been a cornerstone of the Virginia Center for Inclusive Communities’ work dating back to our founding in 1935. On November 25 of that year, a group of religious leaders traveling the country to share a message of understanding and respect spoke on the campus of Lynchburg College (now the University of Lynchburg). The dialogue modeled by this Rabbi, Priest, and Minister team catalyzed the founding of the Virginia Center for Inclusive Communities and informs work that continues to this day.

Over eight decades later, the need for constructive and inclusive dialogue remains. At a time of great separation due to the pandemic and political polarization, this guide is designed to provide frameworks, tools, and resources to support dialogues that can (re-)build community. It is intended to be used by individuals and institutions interested in planning or organizing dialogues as they consider whether or not a dialogue is the best option, how to structure a dialogue session or series, who to invite, and more.

This information on this page can also be found as an online document and as a downloadable pdf.

Topics

When to Utilize Dialogue

Planning Constructive & Inclusive Dialogue

Designing Constructive & Inclusive Dialogue

3 Cs Model

Personal Habits for Healthy Dialogue

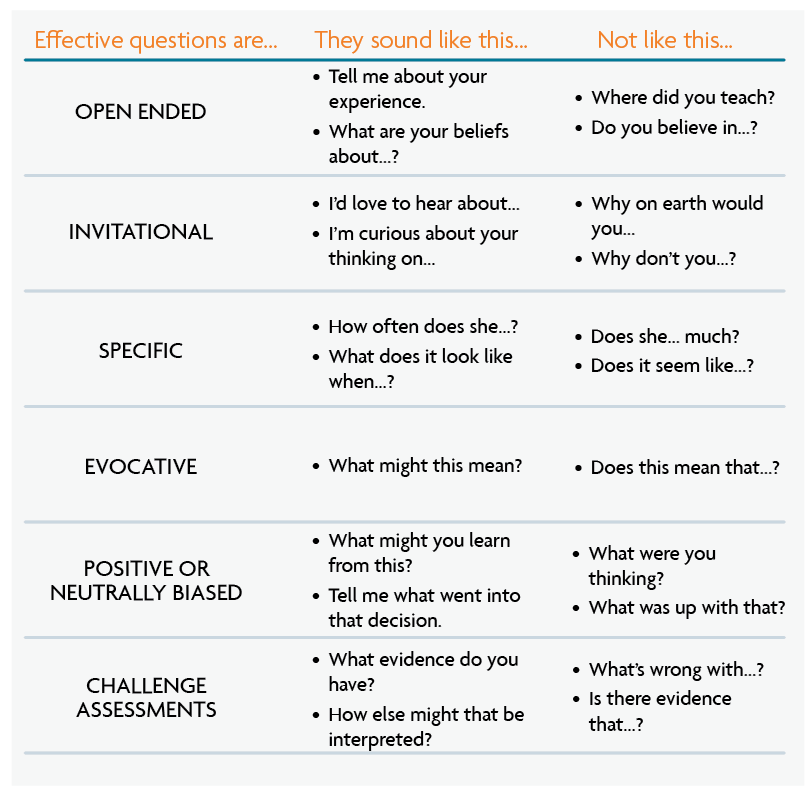

Six Characteristics of Effective Questions

EXPLORING POWER DYNAMICS, ALLYSHIP, AND SOLIDARITY

A Legal Perspective

HISTORY OF CONSTRUCTIVE & INCLUSIVE DIALOGUES

Acknowledgments

When to Utilize Dialogue

Constructive and inclusive dialogues don’t just happen.

They require careful planning, intentional design, and clear communication.

When designed and implemented effectively, dialogues can:

• Build relationships

• Explore issues

• Raise awareness

• Increase trust

• Motivate individual action

• Mobilize group action

However, there are times when dialogue may not be the best approach. These can include:

• When there are significant power imbalances amongst participants

• When there is not shared agreement on the purpose of the dialogue

• When the organizers are more focused on “changing” someone else’s position

• When conflict prior to the dialogue requires more formal mediation

• And more

Being clear on the motivations and goals of the organizer and participants can help to determine if dialogue is the right approach.

return to top

Planning Constructive & Inclusive Dialogues

Organizers should consider the following questions when starting to plan a dialogue:

- What are we hoping to achieve?

Is dialogue the right approach to achieve the desired outcomes?

How much time is needed to achieve the desired outcomes?

Should the dialogue take place over several sessions, or can our desired outcomes be achieved in one dialogue? - How many people do we want or expect to participate?

How might the group size impact the dialogue? - Is the dialogue open to the public or by invitation only?

What are the pros and cons of each? - Who is extending invitations to the dialogue?

What do participants know before joining the dialogue? - How might outside factors (such as the venue, current events, the demographics of the participants, prior relationships among some or all participants, the demographics of the facilitator(s), etc.) impact participation?

The dialogue facilitator(s) should also be selected thoughtfully. When possible, co-facilitators who reflect diverse identities and skillsets should be utilized. Co-facilitators should have ample opportunity to plan prior to the dialogue to ensure alignment in style and approach as well as familiarity with the content and structure.

GO DEEPER:

Here are some resources for understanding and developing dialogues:

- How to Develop Discussion Materials for Public Dialogue (from Everyday Democracy)

- Debate, Discussion, Deliberative Dialogue (from National Issues Forums)

- Fostering Civil Discourse: A Guide for Classroom Conversations (from Facing History and Ourselves)

return to top

Designing Constructive & Inclusive Dialogues

When designing constructive and inclusive dialogues, it is critical to consider the sequencing of questions and exercises.

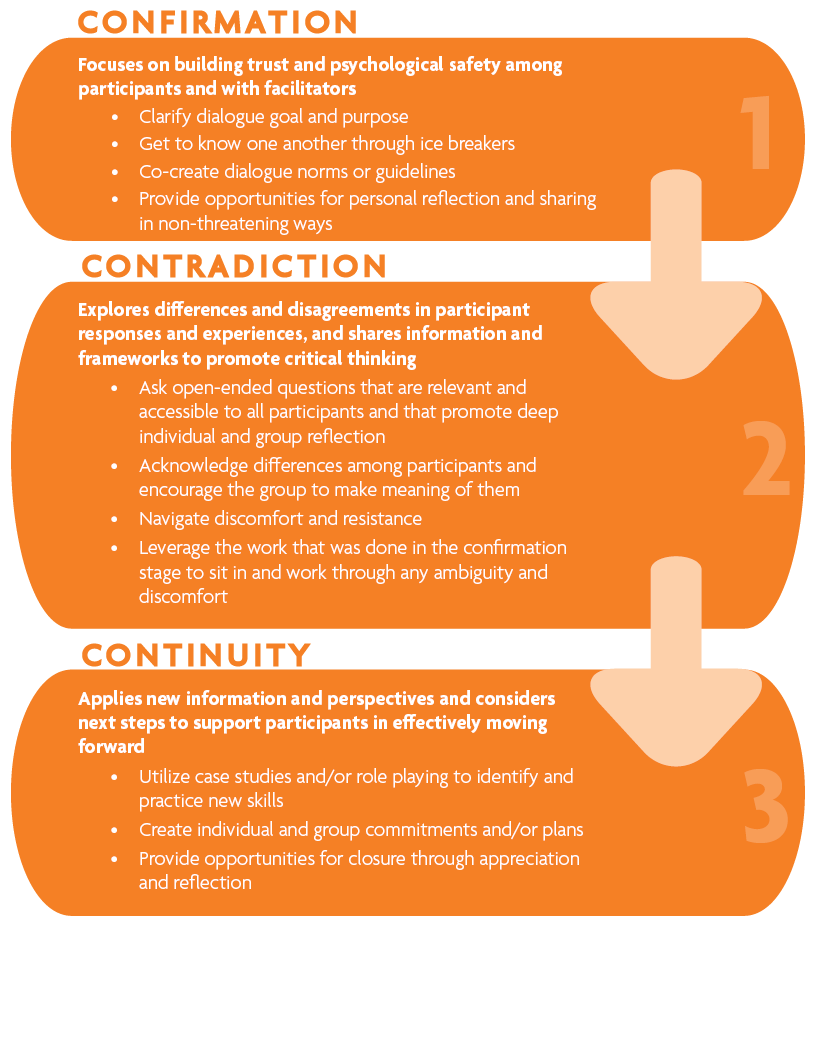

The Virginia Center for Inclusive Communities draws upon the confirmation, contradiction, continuity model in most of our program work (Kegan, 1982 and Goodman, 2001).

The first step in the model is called confirmation, where questions and exercises should be focused on building trust and psychological safety among participants and with facilitators.

The second step is exploring differences and disagreements in participant responses and experiences, and sharing information and frameworks to promote critical thinking. This phase, called contradiction, is often the longest.

The final step of a dialogue in this model is continuity. This step includes applying new information and perspectives, and considering next steps to support participants in effectively moving forward.

At the Robert Nusbaum Center, we like to begin small group dialogues by asking participants to share personal experiences related to the issue being discussed. This exercise helps to break the ice, but more importantly, it encourages participants to recognize that other people are also shaped by their experiences, and have their own values and worldview. That basic recognition of each other’s shared humanity builds trust and ensures a constructive dialogue, even if participants vehemently disagree on the issue being discussed.

GO DEEPER:

A way to sequence questions in the Contradiction phase is ORID:

- Objective

- Reflective

- Interpretive

- Decisional

return to top

3 Cs Model

CONFIRMATION

Focuses on building trust and psychological safety among participants and with facilitators

- Clarify dialogue goal and purpose

- Get to know one another through ice breakers

- Co-create dialogue norms or guidelines

- Provide opportunities for personal reflection and sharing in non-threatening ways

CONTRADICTION

Explores differences and disagreements in participant responses and experiences, and shares information and frameworks to promote critical thinking

- Ask open-ended questions that are relevant and accessible to all participants and that promote deep individual and group reflection

- Acknowledge differences among participants and encourage the group to make meaning of them

- Navigate discomfort and resistance

- Leverage the work that was done in the confirmation stage to sit in and work through any ambiguity and discomfort

CONTINUITY

Applies new information and perspectives and considers next steps to support participants in effectively moving forward

- Utilize case studies and/or role playing to identify and practice new skills

- Create individual and group commitments and/or plans

- Provide opportunities for closure through appreciation and reflection

3 Cs in Practice

A few years ago, a series of conflicts and fights began breaking out at a Virginia high school. As administrators and teachers at the school began to investigate the cause of the altercations, they learned that tension was high around the fact that some students were wearing shirts and belt buckles that displayed the Confederate flag. Some students thought that the flag represented a really hurtful part of history and were offended by the flag, while others found the flag to be a source of pride and connection to their culture.

In an attempt to gain order and work towards solving the root of the problem, administrators decided to bring both groups together after school for discussions. The initial dialogue focused on “Confirmation” with prompts that encouraged the building of trust and relationships. While things didn’t end perfectly after that first dialogue, the group did decide to come back together the next week to continue the conversation – and they agreed that there would be no physical altercations over the next week. When the group met again, they went deeper, beginning to ease into the “Contradiction” phase. They shared more personal examples, identified points of misunderstanding and disagreement, and acknowledged where they may have erred in the past. Over time, the group decided to maintain weekly meetings and invite others to join.

After several meetings, it was acknowledged there may never be consensus, but what was also clear was that the healthy dialogue around different lived experiences and values was helpful. As they moved into “Continuity,” students brainstormed ways to improve their school culture, and they worked together to implement some of the ideas during the remainder of the school year.

return to top

Personal Habits for Healthy Dialogue

If you feel judgmental or defensive, ask yourself:

I wonder what brought them to this belief?

I wonder what they are feeling right now?

I wonder what my reaction teaches me about myself?

GO DEEPER:

Here are some resources to further explore personal practices for dialogue:

- 5 Habits of the Heart that Help Make Democracy Possible (from the Center for Courage & Renewal)

- Making Healthy Dialogue a Corporate Value (from SHRM)

- Leading Change: Setting Criteria for Effective Dialogue (from Ki ThoughtBridge)

Much of what constitutes constructive and inclusive dialogue aligns with practices of healthy interpersonal communication.

While the specific goals and context may vary, the following personal habits are particularly important for dialogue:

Prioritize active listening

Effective listening is active, with the listener keeping the focus on the speaker. Active listening avoids evaluating, judging, labeling, or giving advice. Instead, it includes the following communication skills:

- Open-ended questions: Questions that begin with what, when, where, who, or how. Closed-ended questions, those that begin with do, will, don’t, etc., are only utilized if seeking a yes/no answer. Why should be used sparingly because it is often utilized to put people on the defensive.

- Summarizing and clarifying: Paraphrasing that focuses on the important events, ideas, people, or situations shared by the speaker.

- Reflecting feelings: Stating your perception of the speaker’s feelings with descriptive emotion words such as happy, sad, confused, excited, afraid.

Active listeners are aware of not only what the person says, but also tone of voice, facial expressions, eye contact, body posture, and movement that often convey the feelings and meaning of others.

Engage in consistent self-reflection

Taking time to understand one’s own context contributes to a healthy dialogue. Here are some guiding prompts for self-reflection before engaging in conversation:

- What do I hope to share in the dialogue?

- What might I be able to learn in the dialogue?

- How do I tend to respond in moments of disagreement or conflict?

- When I am upset or defensive, what are some practices I can use to calm down enough to have the conversation? How do I recognize when it is the appropriate time to step away from the conversation and revisit it?

- Do I understand why the other participants have the perspective that they do? How can I take the time to understand their perspective so that I have the appropriate context when I reflect?

- What life experiences of mine may conflict with understanding the other person(s) perspective? What are my advantages or disadvantages (regarding race, religion, age, ability status, gender, sexuality, socio-economic status, etc.) that inform my perspective?

Address your own unconscious biases

Unconscious bias “refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner.” Being aware of how our brains make associations is a critical practice that supports constructive and inclusive dialogue. What pop-ups do you have when you walk into a space? What assumptions might you be making about other participants – and what might they be assuming about you?

Acknowledge the differences between dialogue and debate

Many people fail to see the difference, yet the distinction is important. Participants in a debate often come in with a “winner takes all” attitude. In an attempt to win, tempers can sometimes flare and conversations get out of hand. By contrast, dialogue is a conversation aimed at exploring all sides of an issue to raise awareness and encourage additional thought. It is a healthy exchange of ideas with no expectations of changing minds or “winning” against an opponent.

Recognize that dialogue takes practice

Our society has not provided consistent models and outlets for dialogue, meaning that these habits require practice and repetition. When a dialogue does not proceed as you had hoped, learn from your mistakes. The more you practice, the more capable you will be in tackling important issues when they emerge.

return to top

Good dialogue questions should elicit personal storytelling, avoid judgment, and help to cast light on root causes of division or conflict.

return to top

Exploring Power Dynamics, Allyship, and Solidarity

One of the major challenges with dialogue involves its implicit and explicit ties to power dynamics. Individuals from marginalized groups may ask themselves questions such as:

“What will this conversation change?”

“Will the effort be worth the stress?”

“Will people listen to me or believe me?”

“Is the dialogue taking place at a location where I am comfortable?

“Will there be repercussions if I’m honest about my experiences?”

When dialogue participants are concerned about engaging in what could be a vulnerable or damaging encounter, the opportunity for constructive dialogue may be hindered before it begins. This is where establishing allyship and solidarity play an important role.

When considering how a dialogue may unfold, one may want to consider:

- In what ways is (or isn’t) my allyship and/or solidarity constructive?

- How do I hope for my allyship/solidarity to be further informed by this dialogue?

Not only are these reflections helpful for building self-awareness and understanding one’s own context before entering into a conversation, but also have the potential to address the power dynamics that hinder constructive dialogue. Namely, the more solidarity and allyship are demonstrated, the more that trust can be established – trust that dialogue results in progress.

Indicators of allyship and solidarity include:

- Investment in educating self and others (without any expectation that a member of a marginalized group will be your ‘go-to’ for learning)

- Not ignoring harmful behaviors when they occur

- Leveraging advantage by taking opportunities to speak up (without speaking for or over others)

- Addressing the roots of harm at both interpersonal and institutional levels (e.g. practices and policies)

Ultimately, constructive and inclusive dialogue – paired with healthy allyship and solidarity – can result in concrete, actionable steps that merge the issues that prompted the dialogue with solutions that address the underlying causes of said issues.

GO DEEPER:

Here are some resources for understanding power dynamics, allyship, and solidarity:

- Guide to Allyship (from Amélie Lamont)

- How Does Power Affect our Conversations? (from Essential Partners)

return to top

A Legal Perspective

A Legal Perspective on Constructive and Inclusive Dialogue

By Danielle Wingfield, JD, PhD

Background about the First Amendment

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states that: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

The First Amendment is the first of twenty-seven amendments of the United States Constitution and speaks directly to the essence of what makes us human – our spirit. It further secures the inalienable right to the free exercise of religion and, presumably, the right not to engage in religion. It can very well be argued that this Amendment addresses the spirit of community across the United States of America, bearing witness to the humanity of each individual. As a part of the greater diversified society, each one of us has been engrafted into the free spirit of America.

Other First Amendment freedoms speak to humanity in ways other amendments do not. The First Amendment encompasses the freedom of expression, assembly, and protest. As a person, we have the right to transcend who we are by extending ourselves outward through our voices. Whether as an individual voice or the voice of a collective few or a collective many, we have a right to be heard and to come together with others of like minds. Whether by speech or other forms of media, the free course of thoughts, feelings, and ideas is a right that we must continue to exercise and defend. In doing so, our humanity, our communities, and our way of life are preserved.

Implications for Constructive and Inclusive Dialogue

Generally, private entities may place limits on individual freedoms, including freedom of speech. A primary means of redress for people who feel aggrieved is to leave the organization or disaffiliate. Still, there are limits to private entities restricting individual liberties where the private entity is receiving public funding. For instance, this comes up when a private business wants to discriminate against people based on race or religion and at the same time receive government benefits. In traditional public forums, however, the First Amendment is implicated. The government may still impose time, place, or manner regulations and other content-based restrictions depending upon whether it is a public or a private space.

Even with this heightened awareness of what is and is not considered protected speech, there are several examples of the type of instructive and inclusive dialogue we might aspire to have in this current moment. I contend that the fair and unbiased application of the First Amendment is among the most important topics of the 21st century. The conversation must continue as, for example, the experiences of the underrepresented, who are most often the poor and minorities, continue to be disaffirmed after generations of unequal treatment.

The First Amendment codifies the strength of the human spirit, the right to be heard, and the right to come together. By exercising these rights and celebrating the diversity of this country, we become the embodiment of a truer, brighter America.

Danielle Wingfield, JD, PhD

Professor Danielle Wingfield is an Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Richmond School of Law. Her primary areas of scholarship and teaching includes Constitutional Law, Race and the Law, Civil and Human Rights, Family Law, and Legal History. While a practicing attorney, she specialized in family law and education law. Professor Wingfield received her PhD from the University of Virginia, her JD from the University of Richmond School of Law and a BA from the College of William & Mary.

We suggest beginning with a constitutional framework that teaches… how to enter effective dialogue with their peers and understand their differences without fear or derision. This civic framework can serve as a strong foundation for students, inspiring them to learn, participate and grow from a place of safety and is derived from the Williamsburg Charter’s three key principles:

- The reaffirmation of the inalienable rights guaranteed by the First Amendment;

- The reconstruction of an American public square that hinges on shared responsibility to protect those rights, even when we disagree;

- The reappraisal of how we communicate about disagreements, to begin our conversations from a place of respect rather than conflict.

return to top

History

Constructive and Inclusive Dialogues in America

By Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Ph.D.

The history of constructive and inclusive dialogues in America has its roots in 19th century efforts to redress inequalities and injustices in society. Typically, small groups of people gathered with like-minded individuals to discuss the issues and offer solutions to the problems. Determined and fearless, many of these groups attracted others who added their perspectives and solutions to the dialogue. Many of America’s difficult dialogues began over issues such as abolitionism, women’s rights, African American and Indigenous People’s rights, the rights of laborers versus captains of industry, and social justice. Initially, the discussions included people of the same racial background, gender, or social class discussing their similar criticisms and agreeing on an agenda. As these groups expanded their voices to include those who did not look or dress like themselves, they instead grappled with inclusion, constructive communication, and mutual goals.

In American society, constructive and inclusive dialogues has been difficult to achieve because it requires honesty, taking personal responsibility for change, abandoning preconceived ideas and prejudices, and listening to other people’s perspectives. Constructive and inclusive dialogue has often failed in America because of resistance to discuss racial and gender-related topics that reveal prejudices and an underlying fear that change in society may alter their privileges.

Numerous historical examples reflect these issues beginning with the Abolitionist Movement and the Women’s Movement. In abolitionism, those Whites who fought for an end to slavery did not equally fight for Black empowerment and equality. Instead, many supported Black colonization of Africa or a segregated and racially restrictive society. Similarly, the Women’s Movement was derailed when the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified, allowing for Black men to receive the franchise before White women. So angered were White women, who saw this as an indignity, that they abandoned any efforts to present a unified front in support of women’s suffrage with Black women and instead lobbied for suffrage for White women only.

The history of constructive and inclusive dialogues in America has its roots in 19th century efforts to redress inequalities and injustices in society.

It would not be until a 1908 a race war that erupted over the alleged sexual assault by a Black man on a White woman in Springfield, Illinois that a small group of White and African American activists met together to create a biracial advocacy organization. This small group was outraged that the White mob that was prevented from killing the accused man instead decided to vent their anger on Springfield, Illinois Blacks for months with murders, the destruction of homes and businesses, and the general terrorizing of the Black community. Indeed, from 1900 to 1908, anti-Black riots broke out in numerous other cities including New York, Evansville, and Greensburg, Indiana. Many were outraged that a race riot broke out in the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln. This attention in the White press garnered extensive press coverage, resulting in the organization in 1909 of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Born from an interracial and interdenominational group of activists, the NAACP crafted a single agenda: address the deteriorating status of African Americans by promoting equality and eradicating caste or racial prejudice in America. The group also adopted specific tools to accomplish their goals, including legal action, protests, publicity, voting, and political lobbying.

As the NAACP nationally broadcast incidences of lynchings, murders, and other inhumane affronts to people of color in the nation, moderate Whites who were offended by White America’s march toward a decidedly violent response to the presence of African Americans founded the biracial Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC) that opposed lynching, mob violence, and racial bias in education and society in general. A decidedly southern organization, local committees emerged throughout the nation including in Virginia with agendas that focused on managing White supremacy instead of eliminating it. Supported by many prominent political leaders, such as Virginia Senator and later Governor Harry S. Byrd, the CIC sought to create a segregated society devoid of racial violence. By 1921, a Women’s committee was created, eventually emerging a decade later as the powerful Women’s Council on Interracial Cooperation (WCIC). In Virginia, the WCIC was especially active, beginning in 1945, and led by Vivian Carter Mason, a social worker who eventually became president of the National Council of Negro Women. Clearly, the agenda was set by the empowered group, leading to an unsuccessful dialogue that failed in its objectives because the goal was not mutually agreed upon by an inclusive group and its motivation by the dominant group was based on fear.

With the Great Depression that threatened to topple society and the looming Second World War, numerous organizations felt an urgency to create a collaborative dialogue that would produce solutions to national and international challenges in the 1940s. The Congress on Racial Equality, The National Council of Negro Women, the Women’s Interracial Council, and the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) initiated independent and collective efforts to fight for equality globally, transcending race, class, gender, and nationality, issues that divided people. These organizations met with some success in promoting interracial cooperation and real change because the agendas were not established by the power elite. Rather, it was crafted in an equitable manner and by those who were the victims of prejudice or discrimination.

By the 1960s, it was clear that dialogue was an important tool for community building. However, the agendas did not reflect the promises. Numerous cities and states created interracial commissions and community groups to discuss and provide input on city planning, housing, crime, redistricting, voting, and other matters. Yet, the implementation bore little resemblance to the recommendations, thus igniting community conflict and anger. This practice continued throughout the remainder of the century and into the next until the protests surrounding the murder of George Floyd. While Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama attempted to trigger national dialogues on race and equity, it was not until the nation witnessed images of George Floyd being killed was there an international outcry demanding systemic change.

Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Ph.D.

Dr. Cassandra Newby-Alexander is the Endowed Professor of Virginia Black History and Culture, Director of the Joseph Jenkins Roberts Center for the Study of the African Diaspora, and former Dean of the College of Liberal Arts at Norfolk State University in Virginia. She is the author of Virginia Waterways and the Underground Railroad (2017), An African American History of the Civil War in Hampton Roads (2010), co-authored Black America Series: Portsmouth (2003), Hampton Roads: Remembering Our Schools (2009), and co-edited Voices from within the Veil: African Americans and the Experience of Democracy (2008). Dr. Newby-Alexander has appeared on a number of national programs and documentaries including PBS’s Many Rivers to Cross, the History Channel’s Race, Slavery and the Civil War, and C-SPAN’s broadcasts on history.

return to top

Acknowledgments

The Virginia Center for Inclusive Communities gratefully acknowledges an anonymous donor who made the Constructive and Inclusive Dialogue Initiative possible.

We thank the following community members for offering input on the initiative:

Kim Bobo

Executive Director

Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy

Cortney Calixte

Director of Movement and Capacity-Building

Virginia Sexual and Domestic Violence Action Alliance

Chloe Carter

Community Engagement Coordinator-Youth

Chesterfield County

Rob Corcoran

Training Consultant

Initiatives of Change International

Founder Emeritus, Hope in the Cities

Dr. Veleka Gatling

Assistant Vice President-Diversity and Inclusive Excellence

Old Dominion University

Kelly Jackson

Associate Director of the Robert Nusbaum Center and Deputy Diversity Officer

Virginia Wesleyan University

Melvyn Smith, Jr.

Director of Diversity and Inclusion

Genworth

Rev. Dr. Craig Wansink

Professor of Religious Studies, Joan P. and Macon F. Brock, Jr. Director of the Robert Nusbaum Center, and Chair of Religious Studies

Virginia Wesleyan University

We extend appreciation to the following scholars for authoring content in this Guide:

Dr. Cassandra Newby-Alexander

Endowed Professor of Virginia Black History and Culture and Director of the Joseph Jenkins Roberts Center for the Study of the African Diaspora

Norfolk State University

Dr. Danielle Wingfield, J.D.

Assistant Professor of Law

University of Richmond

return to top

This guide has been created by the Virginia Center for Inclusive Communities.